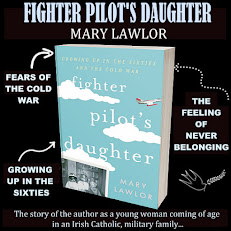

Title: Fighter Pilot’s Daughter: Growing Up in the Sixties and the Cold War

Author: Mary Lawlor

Publisher: Rowman and Littlefield

Pages: 323

Genre: Memoir

Fighter Pilot’s Daughter: Growing Up in the Sixties and the Cold War tells the story of Mary Lawlor’s dramatic, roving life as a warrior’s child. A family biography and a young woman’s vision of the Cold War, Fighter Pilot’s Daughter narrates the more than many transfers the family made from Miami to California to Germany as the Cold War demanded. Each chapter describes the workings of this traveling household in a different place and time. The book’s climax takes us to Paris in May ’68, where Mary—until recently a dutiful military daughter—has joined the legendary student demonstrations against among other things, the Vietnam War. Meanwhile her father is flying missions out of Saigon for that very same war. Though they are on opposite sides of the political divide, a surprising reconciliation comes years later.

Fighter Pilot’s Daughter is available at Amazon.

Here’s what reviewers are saying about Fighter Pilot’s Daughter!

“Mary Lawlor’s memoir, Fighter Pilot’s Daughter: Growing Up in the Sixties and the Cold War, is terrifically written. The experience of living in a military family is beautifully brought to life. This memoir shows the pressures on families in the sixties, the fears of the Cold War, and also the love that families had that helped them get through those times, with many ups and downs. It’s a story that all of us who are old enough can relate to, whether we were involved or not. The book is so well written. Mary Lawlor shares a story that needs to be written, and she tells it very well.”

―The Jordan Rich Show

“Mary Lawlor, in her brilliantly realized memoir, articulates what accountants would call a soft cost, the cost that dependents of career military personnel pay, which is the feeling of never belonging to the specific piece of real estate called home. . . . [T]he real story is Lawlor and her father, who is ensconced despite their ongoing conflict in Lawlor’s pantheon of Catholic saints and Irish presidents, a perfect metaphor for coming of age at a time when rebelling was all about rebelling against the paternalistic society of Cold War America.”

―Stars and Stripes

First Chapter:

In the 1920s, when Jack was a child, a framed photograph of his

father stood in the living room of their house on Richmond Avenue in

South Orange, New Jersey. My grandfather, Edmond Vincent Lawlor, had

come

to the United States in the early years of the twentieth century, when

he was barely into his teens. On September 19, 1916, he became a U.S.

citizen. Not long after, he signed up for Officers Candidate

School

at Princeton and got ready to join thousands of others in The World War,

later renamed World War I. The picture on the table shows him in

uniform, stiff with duty. As a household decoration, it signaled the

deep connection between the nation and the family, demonstrated through

military service.

Papa, as we called our grandfather, gives a faint smile in the picture.

There’s

nothing macho in this expression, no hint he was imagining himself

heroic. He was a devout Catholic and would have understood his soldierly

commitment as God’s will. Fighting on the side of the

Yanks also

gave him a chance to show his affection for America. This was the

country that had taken him in, given him a job in a powder factory,

offered a new life to his mother and aunt.

World War I was still a

pulsating memory when Jack was a boy. For him it would have been a murky

tale of faraway places and mysterious danger. The photo showed his

father on the edge of all this, an adventurer and a stunningly different

person from the cheerful, gray-suited insurance salesman who came home

every day at six o’clock.

Papa Lawlor at Officers Candidate School

near the end of WWI Edmond never went to the war. It ended by the time

he finished OCS. But Iremember that picture of him in uniform, there in

the many living rooms of my own early years, a reminder that Papa was

not only the mild, affable Irishman we loved, but a man who knew how to

use a gun, had been ready to expose himself to violence on behalf of our

country.

I say Papa smiles in the photo, but when I look at it now

the expression isn’t so easy to read. The face is actually pretty blank.

You could say it’s a mask, an empty screen hiding Papa’s feelings, even

his sense of

himself as a Navy ensign. The eyes are aimed slightly

to his right, off camera, as if he’s not entirely engaged in the

portrait. If you keep looking, movement stirs in his face. It’s in the

eyes of the beholder, of

course, but he begins to look like he’s

ready for something else and can barely stand the still pose. Is this

simply his characteristic lack of vanity?

Does he want to get going with the soldiering? Or is he itching to get out of the uniform, go home where he belongs.

As

Jack came to the end of his school years, the laughing family and shady

streets of South Orange started to look tame. He tried a few semesters

at Seton Hall University, not far from home, but his performance was

less than impressive. Letters show he was already captured by thoughts

of himself far away, across the continent, perhaps the ocean. But he

never looked down on his local, New Jersey world. It was the setting of

boyhood stories he told us when we were kids. It was the place he gladly

returned to after hot summer days in downtown New York, working as a

messenger for the Japanese Cotton and Silk Trading Company. South Orange

was his mother’s world. It was where Nan Ferris Lawlor presided over

his beloved brothers and sisters—“my kin,” as he jokingly called them.

In his first uniform, standing on the dappled lawn of the house on

Richmond Avenue, he grins at the camera, his arm around her. He looks

happy to be so grounded there, and so ready to go away. He wanted

adventure. He wanted to go to sea, to learn navigation. And he wanted to

fly.

In March 1942 Jack enrolled as a cadet at the U.S. Merchant

Marine Academy. Established by Congress in 1938, the Merchant Marine

Cadet Corps trained sailors for commercial ships that could convert to

military

service in times of war. Now, with the demands of World War II

pressing, merchant marines were needed for duty in less time than the

formal curriculum allowed. Jack spent three months in the class

room

at the Academy’s temporary facilities on the Chrysler estate in Great

Neck, Long Island. Courses included seamanship, cargo handling, maritime

engineering, math, and ship construction. He studied

hard and did

well. Letters home, written in an exuberant voice, show how excited he

was to be learning the life of a seaman, getting ready to see the world.

In

preparing for a naval science exam in the spring of 1943, he wrote his

father, “If I don’t pass it at least I tried. I know you’ll be

interested to hear this Dad, knowing how disappointed you were with the

time I wasted in Seton Hall. I realize that myself now, Dad, more than

ever and I’m going to do my best to make up for it.” He was affectionate

with his parents and wrote as if pleasing them mattered a great deal.

For all

his desire to get away from home and out into the world, his identification with the family was absolute.

Gleeful

at what the Merchant Marines were preparing him to do, Jack found

talents he didn’t know he had in the seamanship training, especially in

navigation. For the signaling course, he had to commit

endless codes

to memory. He would have to pass a test that required sending eight

words per minute in Semaphore and another eight in Morse. “It’s going to

be tough,” he complained, “because there is nothing interesting about

it. It’s just plain memory work. But you’ve got to know this stuff on

board ship so it’s a good thing.”

Practicing as an able bodied seaman

was another story. “Yesterday afternoon we shipped an 800 pound anchor

over the side to a barge and there were only three of us to move it.

Today we had quite a thrill. They sent Tex and me aloft to paint the

masts in a boatswain’s swing. Boy oh Boy but you’re away way up when you

do that and when we painted the top part and got down to the spar we

had to crawl out on our bellies to paint the end of the thing. God I

liked to die. That mast was swaying with the ship and me out on the yard

that was bending under my weight. I’m so darn tired from hanging on

that I can hardly lift the pen. But I think I’ll live.”

With his

six-foot frame, good looks, and rough amiability, Jack made friends

easily. Time with his new pals was often brief, as the advanced pace of

Merchant Marine training meant assignments were given out

quickly. In

letters home he complained at having to say goodbye. “I made quite a

friend with this guy Tex. . . . But he’s due to go home in two weeks.

Gosh it’s lousy this way your friends come and go so quickly

in a

place like this.” As Jack’s first voyage approached, he was glum about

the separations. “There are only 4 of us left out of our whole gang

since this afternoon, for 3 shipped out then. . . . Boy it really seemed

tough

saying goodbye to those 3 guys this afternoon and we’re a pretty

lonesome bunch tonight.” The letter has a prophetic tone to it. There

would be a lot of this in years to come. Jack would soon toughen up,

learn to slap the guys on the back and say good-bye fast. He knew he

might never see them again, and he stopped writing home about it.

Reading

this letter about the three guys shipping out so many decades later, I

feel badly for my dad. Then I see mornings on the tarmac when Jack is

leaving us for some long-term mission. And the sight of a neighborhood

comes up, receding in the back window of our car. Friends, then

boyfriends wave good-bye. Of course, for Dad and his remaining pals

another kind of loss lurked at the sight of the waiting

sea bags and in the last, terse good-byes. Where they were going death lurked right beside the adventures.

On

May 11, 1942, he got his shipping papers. Rumors had been circulating

that his cohort would have their first orders soon. Jack’s letters are

ambivalent about it. Twice he uses the word terrific where

terrible

should be. A few paragraphs after announcing the news of the shipping

papers, he writes, “It seems terrific to think that I’ll be actually

leaving home for such a long time. I keep trying to picture what it’s

going to be like. I just dread the thought of the dam last day when I

have to say so long to you all.” A week later, he and his pals set out

by train for San Francisco where they would be assigned to a ship. In

the club car with his friend Ray Barrett he penned a note, posted by the

porter from Pittsburgh, describing his sad self in not entirely

convincing terms: “Well that dreadful day when I had to leave you is

almost past and let me tell you the big tough guy who never got homesick

isn’t so big and tough any more and this afternoon at Penn Sta he was

plenty homesick. But after we fastened up we had a good chicken dinner

for $1.65 less 10% for the uniform. I felt much better. But it was

terrific leaving you.”

In San Francisco, before reporting for ship

duty, he had the time of his life. He and his friends were treated like

visiting celebrities. “I’m in the best place in town, the Hotel Francis

Drake, and a gal just took my picture. I’ll send you one.” In the same

letter he tells them “our picture was in the S.F. Chronicle. I’ll send

you one of those too! The S.F. Chamber of Commerceis having a National

Maritime Day and we were picked to pose for the paper.” He sent a

clipping along, a photo of himself and a fellow cadet in dress uniform,

smiling as they explain the details of a model cargo ship bridge to a

San Franciscan named Virginia Haley. It’s hard to tell whether the

center of the photo is the ship model, Dad’s grin, or Haley’s legs. At

the Persian Room on May 21, he laughs at the camera in the company of an

unnamed actress in a white pillbox hat. The next night, at Charlie

Low’s Forbidden City, a supper club on Sutter Street, he stands beside a

local actress, looking awkward but dapper nonetheless. Another night in

the Persian Room, Jack

glances at the photographer while talking

with Ray Barrett and another friend from the Academy. Over cocktails and

smokes, they’re obviously enjoying themselves, but something serious

hovers between them. Ray wrote on the inside of the photo sleeve, “We

went to the Academy together and now we’re going to sea together. Need I

say more than all the luck in the world to you?” Amid the dancing and

cocktails and the photographers, they were having a ball. They were also

thinking about what was coming next.

He was assigned to the Grace

Line’s Santa Clara. “The ship is a corker—it’s big, fast and well armed

(Thank God),” he wrote to the family. “Our stateroom was a mess when we

first got into it but today we fixed it up and it’s pretty nice. We have

plenty of room, our own bath and lots of closet and locker space. There

are three of us in the room and we get along swell. The meals are swell

and we eat in the officers’ mess. It’s a break being on a troop ship,

because the food is always extra good on them and besides they are well

protected.” Earlier, still in San Francisco, he had met some of his

superiors and written home, “the officers are swell guys and

surprisingly young. We are with the third mate tonight and the girls

[Jack’s sisters, Ann and Marg] would go nuts over him. We are learning

more than I thought it was possible for me to commit to my thick

cranium, just through these young fellars. The skipper is only 35. How

about that?” In ten weeks they would be back in New York. Jack was out

of his head with excitement but mindful of his attachment to home. In a

postscript, he notes “I’m damn happy, but a little lonesome.”

By the end of his first year, Jack had been at sea for nine months.

Still

he kept in touch with South Orange regularly. He addresses the

household as “Dear Home” and signs his letters “Salty.” Expressions of

affection intensify as time, distance grow. On the eve of his first trip

to

the Pacific he wrote: “You have said you were proud of me. Well

I’m pretty damn proud to call myself one of you.” At times the words

have a faint ring of guilt—for being so far from home, for having a

great time

at it: “You are the grandest Mother and Dad a fellow could

have and I’ll always look forward to the days I can spend with you

again.”

Jack was out on a cruise when Edward Haugh, who would soon

become his close friend and brother-in-law, entered the Merchant Marine

Academy in 1943. Five years later Ed married Frannie’s younger

sister,

Mary Ellen. Like a mirror opposite of our own family, Mary Ellen and Ed

had four sons, more or less our ages. Much later, after my dad and

uncle had become experienced seamen and pilots, after they’d

seen

violent action in war, it was the Haugh boys who learned about the most

dramatic events, the violent ones. As girls and even women, we were

never told those things. Bits and pieces reached our ears, fragments of

stories about crashes and escapes through enemy territory. We would

wonder, mystified, about where our father had been, how these things

happened, what he felt and did. I imagined veiled scenes in dark

jungles, Dad slipping through the high growth, his terrified gaze

hunting the perimeter. He would be operating on deadly survival

instincts, hungry, thirsty, wet. A specter as frightening as the enemies

who missed him, he crept in absolute silence, the blue eyes, like

flashlights, pointing the way. Or he was down in the sea, clinging to

the wing of a plane, waiting for some helicopter to lift him out. These

images came and went whether he was home or away.

During the return

cruise to New York in early August, Jack’s exhilaration with life as a

Merchant Marine came under the cloud of one particular commander. The

man threw his weight around, made his presence felt among the cadets,

making them do unnecessary things, just because he could. Jack got in

his sights and found himself in a power struggle with a personal charge

to it. He restrained himself from

telling the guy off when he

demanded that a course, checked for accuracy several times already, be

backed up with a series of alternative routes—a job that called for

meticulous, time consuming calculations.

Jack took a deep breath and

performed the useless task but swore he would get out of this man’s

clutches. Landed in New York again in September, he and his buddies

proceeded to the Merchant Marine

office downtown to sign up for

another trip out, but the functionary in charge refused to put them

together on a different ship. Word had made its way from the dock. Jack

and his best friend, George Roper, decided “to hell with them.” As

Merchant Marine cadets, they had already been sworn into the Navy on

reserve status. The Navy could give them something the academy couldn’t.

They could learn to fly. The next day the two of them walked north to

the Naval Recruiting Office

and enlisted for active duty.

In the

Merchant Marines, the cadets had been introduced to the ancient

discipline of navigation. Always good at math in school, Jack, George,

and my uncle Ed had taken it up like naturals. Mathematical

representations

were as real to them as the ground itself. Even in retirement, their

desks were littered with compasses, rulers, pencils and scraps of paper

covered with calculations. The practice of charting seas

gave them

confidence in moving through watery space, like it was lined and

readable as a series of roads. Success at plotting a course at sea, as

Uncle Ed explained not long ago, rattled their imaginations. They

wondered how it would be to navigate the sky.

In the autumn of 1942,

Jack and George began flight school at the Naval air station in New

Paltz, New York, north of West Point. Ed came up the following year.

Jack’s notes for the first course, in a folder la

beled in block

print “Aircraft Identification, Mr. Oakley,” show he was already

dedicated to learning everything he could about airplanes. In a careful

hand he lists “Four main wing and plane relationships,” “Wing

Descriptions,” and “Tips.” He copies the markings for Navy and Army

aircraft alphabetically. A hand-drawn graph, the boxes neatly ruled,

identifies the names of airplanes with their wing and tip

configurations; engine and armaments; tail and fuselage surfaces; speed,

ceiling and load range. Forty-two different planes appear in the

six-page chart.

Photos, cut from catalogs and neatly taped to the

notebook pages, show the Grumman G-21, the F4F Wildcat, the Martin PBM-3

Mariner (a “flying boat”), the Vought-Sikorsky OS2U-1 Kingfisher, the

SB2U-3

Vindicator (“a dive bomber”), and many others. British planes

appear—the Hawker Hurricane IIc (“with bombs slung under the wings”),

and the Handley Page Halifax. A page is set aside for Japan’s Kawanishi

Type

94 (a bomber for which “no information is available on the location of

the bomb bays”); another for Germany’s Dornier DO 17 (“a reconnaissance

bomber”) and the infamous Messerschmitts—the ME

110 and

ME109F.Captions indicate the wing and tail markings and the

all-important size, speed, and range specifications. For survival’s

sake, Jack would have to get these in his head. Notes in the margins

indicate he was memorizing speed, altitude, and bombing capabilities of

all the aircraft.

In March 1943, he wrote his father, “I’ve got

almost four hours in the air now and I ought to solo in seven or eight,

which should be some time this week . . . I’ve got a damn good

instructor and he drums those

fundamentals into us all the time. I’m

due to go upstairs to learn a series of ‘spins.’” Upstairs referred to

four thousand feet, a dramatic, new level. The excitement of flying so

high, of getting to take the airplane to the limits of its capacity,

continues a few days later: “Boy those spins are something. We climbed

to 4000, cut the motor and turner her nose straight up and put the

rudder hard left and bingo! Down she goes nose first spinning like a

top. We do two complete spins and come out of it.”

Shortly after, he

made his first solo. The plane was an Aeronca Defender. He told his

brother Edmond about it later, but no description of this prime moment

appears in the letters. Soon he sent his

mother an account of what

flying alone was like. “Walt, my Instructor, let me go out over our area

alone yesterday afternoon for a whole hour.

You can’t see the area

from the field so I had quite a time for myself. First I practiced high

work and went up over the cloudbank at about 7,000 feet. You never saw

anything so beautiful in all your life just you

the plane and the sky

and those big white pillows below you. Super stuff.” Already he felt

confident enough with the aircraft to start fooling around. “After that,

I went down very low and practiced forced landings and made sure the

fields were pastures and Boy you ought to see those dam old cows run.

When I realized how much fun it was I tried dive bombing them and hot

dog if ‘Bossie’ didn’t dam near give birth to a goat. Oh you should of

seen them go—” He signs the letter “Orville Wright.”

Training

continued into the summer of 1943 at Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where

he started doing acrobatic hops; then at Bunker Hill, Indiana, where his

enthusiasm grew explosive. “The flying is really terrific,” he wrote

his mother and father. “There are three stages you have to get through.

First you have A stage, that’s just safe for solo and then B stage,

that’s ‘S’ turns and slips to circles and wingovers. Then in C stage you

really start flying. That’s acrobatics and night flying and those

acrobatics include everything, slow rolls, snap rolls, Immelman’s and

inverted spins and falling leaves and every other tough one you can

think of.”

During

those months at Chapel Hill, Jack went through a rigorous athletic

program, including a week each of track, swimming, football and boxing.

The cadets were graded for each sport. Competition for strong marks was

high. On August 5 he wrote his parents, “I got my boxing marks yesterday

and today. I didn’t make out too good yesterday. I lost my fight but

today I made up for it. I won by a T.K.O. (that means they had to stop

the fight because the guy I was fighting was pretty badly cut up).”

Without another word about this, he moves on to his successes in

football. He had made the battalion squad, a first for his

platoon.

His father must have written expressing concern about the August 5

account of leaving his boxing opponent “pretty badly cut up.”

On the

thirty-first, Jack wrote, “You sounded a little worried about my

reaction to that fight I had. Well it’s O.K. Fact is I’ve made pretty

good friends with the guy since and he wasn’t hurt too much anyway.”

This

is the first evidence of Jack’s capacity for combat. The athletic

schedule at Chapel Hill was aimed at sharpening reflexes for just this

purpose. In late August he described to his mother how wrestling was

simultaneously

training in hand to hand combat: “This hand to hand is the coldest

stuff man ever thought up. It was explained to us this morning as the

ways of quickly killing or disabling permanently a man with

only the

weapons God gave us. We’re being taught to gouge out a man’s eyes and

bite off his ears and bite into his jugular vein in his throat and every

conceivable dirty stunt in the books.” If the “dirty stunts” seemed

repellent to Jack and the detailed description a way of absorbing the

shock, they must have been nothing short of shocking to his mother.

Why he would submit this information to her is something of a mystery.

Sharing

scenes of violence with women was not a practice he would continue.

During these years as a young flyer, everybody in the family served in

the crucial role of audience for his adventures.

Jack’s preferred

vision of military life at this point was far and away a vision of

flying, of trying out the heights and lows, the angles and spins an

airplane could take. Ground combat was distasteful and not for him.

In

June of 1944, he earned his wings at the Naval air station in

Pensacola, Florida. At this point, a cadet could chose to continue with

the Navy or to shift to the Marine Corps, and Jack chose the Marines.

That fall he found himself on the west coast again, this time in

southern California.

At the Marine Corps air station in El Toro he

underwent a combat conditioning course. “You would think we were going

through infantry school instead of being aviators. It’s very much

similar to Chapel Hill

only a lot tougher. We start at the crack of

dawn and do close order drill, exercises and bayonet drill until

sundown. And then to bed and no kidding I’m there by seven. It’s doing

good, I guess.”

But El Toro meant more flight school too. By now he

was tired of being a student. “Well here we are again,” he wrote in

early January of 1945, “back in school. How do you like it? Gee I

haven’t done a damn

thing but go to school since the beginning of the

damn war. But this time I think I’ve got something because these jokers

say that they are going to teach us how to fly every airplane the Navy

uses, from primary trainers to the big 4 engined flying boats. This

month alone we will be flying Avengers, Hellcats, Hell divers.” He had

been through seventy two weeks of flight training, almost a year and a

half as a student. As a professional aviator, he would go back to

“school” periodically to learn the technology of new aircraft. Later

training, however, was more about refining skills he already had, skills

that would eventually come to be recognized as those of a master

aviator.

Jack had been away from home for some time now. He wrote

that he missed the holidays with the family. “I don’t expect we’ll get a

transcontinental for a couple of months yet, but I’ll get there by

gosh. If they

won’t send me over seas I’ll get there by hook or

crook.” Aware of the ambivalence in his phrasing and the muddiness—won’t

instead of don’t and the open-ended meaning of there—about what he

really wanted next, to go home or “overseas,” which meant to the war, he

adds in parenthesis, “to New York I mean.” In spite of Jack’s

exhaustion with being a student, it’s pretty clear as he virtually

chants the names of the airplanes he is about to get his hands on that

what he wants most is to fly and fly some more. The implication is

strong that he wanted not so much to go home but to get further away.

In

all Jack’s letters written from the Merchant Marine Academy, from Navy

flight school, and Marine Corps training, references to the Catholic

religion in which he was raised are sparse and formal. From Navy

pre-flight school in Chapel Hill, North Carolina in September 1943 he

described a field mass he attended at the base stadium. It was a solemn

high pontifical mass, “very pretty and very impressive . . . I sang

in

the choir and we sang the mass of St. Basil and it sounded pretty

good.” But the event is also memorable because his girlfriend Ruth was

visiting from New Jersey. They’d been engaged since before he’d left the

Merchant Marines, but the relationship wouldn’t survive the long

separation to come.

Later that month the base chaplain, Father

Sullivan, asked Jack to manage a fund raising campaign with his outgoing

battalion for the construction of a church. Jack spent a week with a

friend giving “pep

talks” and canvassing. The priest “almost jumped

out of his pants” when they handed over $444.60. Other stories sent home

remind his parents that he’s still a good, practicing Catholic son; but

none of his writing

expresses a deep or conscientious sense of

devotion. In a postscript, he notes, “The chaplain is a grand guy. Have

been to Sacraments” and “Still taking pills and saying Hail Marys.”

If

pressed, Jack would undoubtedly have declared the whole project in

which he was engaged—learning to be a warrior for the good guys—the

deepest sacred duty he could perform. It was the sort of credo he

would

maintain throughout his military career. God, Christ, and the Virgin

seemed to loom for him in a distant sphere. Signs of their benevolence

or wrath might be legible in this-world phenomena, but they

existed

elsewhere. Although he kept an image of Our Lady of Loretto—patroness of

aviators—in the cockpit with him, it wasn’t until after retirement that

he showed a personal, more intimate connection with Catholicism. Maybe

it was there in him earlier, but the letters suggest that for the young

pilot, the more abstract, the more formal his religion, the better it

would work for him.

In May of 1945 he finally set out for the war, to

the site of one of the bloodiest conflicts, Okinawa. Assigned to Marine

Fighter Squadron 222 of the Second Marine Air Wing, he left San Diego

on a troop transport.

He had been waiting for this, for the chance to

get beyond the dress rehearsals of training to the sites of real

action. Excitement beat like a drum. He knew, of course, what horror lay

ahead. The terror was fuel,

already sharpening his senses.

The

well-ordered life at sea, like the round of days on the base, held up a

steady, familiar, world. The repetition of chores, drills, and meals

flattened shipboard experience. Behind the lulling rhythms, however, an

eerie, Melvillian, spell dragged along. One hot day near New Guinea,

when they couldn’t take looking at the gunmetal and the horizon anymore,

Jack and a few others climbed over the edge for a swim.

Shortly

after, the voice of the commander boomed from the deck, ordering them

back on board. Reluctantly but quickly they did as he said. The officer

walked them across deck to the opposite side of the ship and pointed

into the water. It was boiling with hammerhead sharks.

A “shark

shooter,” as Uncle Ed Haugh told me, would normally be stationed at a

lookout point high above the deck when sailors were swimming in Pacific

waters. Protecting the vulnerable crew, the shooter kept a close eye off

the gunwales, ready to fire at any moment. If this protection was in

place, it didn’t dispel the commander’s terror at sight of the enormous,

T-shaped fish, thronging too close to the splashing men.

The

hammerhead shark story was in our heads, told more than once, so vivid

was it in Dad’s memory. He was a good storyteller. He knew how to pace

the action, when to pause, when to raise and lower his

voice. Making a

collective character of the swimmers, he showed with wide eyes and

eager shoulders how dangerously naïve they were. The commander, deep

voiced and rigid, was right, he told us, not because

the hammerheads

proved him to be, but because he was the commander. With loose-minded

people like his younger self to teach and supervise, the commander had

to convey that his word, his order, was reason in itself. Jack’s heart

was not revolting now, as it had to the arbitrary power of the Merchant

Marine officer in the summer of 1942. He had grown up, become a

professional; and the wartime context demanded that everybody do

precisely as they were told. The scene looks ominously symbolic of the

enemy waiting over the horizon, a threat that hadn’t crossed the

threshold of visibility for Jack quite yet. But to our ears as children,

the episode was like an allegory of the horrible things that could

happen if you chose not to follow your leaders, whether they were

parents, or teachers, or ship commanders. Outside the boundaries of our

ruled lives, nature and the world’s violent passions came snapping at

your heels. Better to stay on the boat, as Chef repeats in Apocalypse

Now, his voice mechanical, dehumanized with fear.

In all those years

of sailing, flying, fighting and bombing far from home, pitched against

nature and other people, was my father on the boat or off it? Following

orders, he kept his place. He knew to stay near

the boat and climb

back aboard when commanded. But in later years he would often have to

operate as an irregular, out of anybody’s reach, untraceable, courting

danger. In this sense he seemed regularly off the boat. And that meant

he was unreachable for us, at home, too. Being off the boat was at some

level a choice for Jack, like it is for Captain Willard, just returned

to Vietnam at the beginning of Apocalypse Now, describing his feelings

about home: “When I was here, I wanted to be there; when I was there,

all I could think of was getting back into the jungle.”

VMF222 would

be credited with shooting down fifty-three Japanese planes during the

Battle of Okinawa. Jack flew the F4U Corsair, a carrier-based fighter

aircraft he’d been trained to operate at El Toro.

The Corsair was armed with Browning machine guns on the wings. It could shoot missiles and drop bombs.

The

Battle of Okinawa lasted for three months, until May 1945. At this

point, the U.S. forces had established bases to be used as launch sites

for a major attack on the Japanese mainland. The plan was

scrapped,

of course, when the atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki;

but the bases remained in place. Jack and his fellow pilots lived in

improvised quarters—tents and later quonset huts—not far from the

airfield at Awase.

From February until May of 1946, the war now over,

Jack was as signed to “Special Service” with the Fourth Marine Wing.

This meant duty in Northern China. Among Dad’s medals is a long yellow

bar with

a red stripe at each end, the China Service medal. Marines

had been posted to China since September 1945, helping accept the

surrender of Japanese forces. The situation was complicated by the civil

war that was building between Chang Kai-shek’s central government and

the expanding Communist movement under Mao Tse Tung. Stalin, still

America’s ally, was supporting Mao. The United States hadn’t taken an

overt

military position in this struggle, although the hope was that Chang

would prevail. For ordinary marines on duty in China, the scene was

sometimes difficult to read.

Jack was housed in U.S. facilities at

Tsingtao, on the coast southeast of Beijing. He and other marines shared

the rough quarters with foreign nationals posted on commercial and

diplomatic missions since

before the war, and with members of the

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. (The UNRR was

formed in 1943 by Roosevelt; the “United Nations” were the WWII Allies.

The mission was to provide economic aid and relief for nations damaged

in WWII.)

Among the international community in Tsingtao, Jack met a

Russian woman named Vlada, who he went out with a few times, but either

he decided for himself or he was told to stop seeing her. Dating a

Soviet

citizen had become a problem, and Jack did as he was told. One

night Vlada came knocking at his BOQ door. He didn’t answer. She

knocked louder and shouted into the night, “It is I, Vlada.” He still

didn’t answer.

Eventually she went away. As Dad told the story, it

was clear he thought it was funny. He did a comic imitation of Vlada’s

accented, dramatic English. It’s hard to know if he was laughing at the

time. My sisters and I never thought to ask this question. Were her

antics laughable? Or had he distanced himself from her anyway, before

the new rule came about, because she was demanding, too serious about

him? Did Vlada’s foreignness mean he didn’t need to take her seriously,

whether she was funny or not? I think of Vlada, wonder what she was

going through that night. Who had she thought she’d found in Jack? What

did she think, walking away from his door? Did she remember him for

long? And what of Jack in his own eyes? Did he see himself still as a

gleeful young pilot, ready to leap the oceans, explore jungles

continents away from South Orange? Or had he grown some armor he hadn’t

had before the war, a toughness about the heart that would recede and

then strengthen again in the tough years to come? If Vlada could be

dismissed with a laugh, how ready was he to open his heart seriously to

anybody—and to

any woman—backhome?

About the Author:

Mary Lawlor is author of Fighter Pilot’s Daughter (Rowman & Littlefield 2013, paper 2015), Public Native America (Rutgers Univ. Press 2006), and Recalling the Wild (Rutgers Univ. Press, 2000). Her short stories and essays have appeared in Big Bridge and Politics/Letters. She studied the American University in Paris and earned a Ph.D. from New York University. She divides her time between an old farmhouse in Easton, Pennsylvania, and a cabin in the mountains of southern Spain.

You can visit her website at https://www.marylawlor.net/ or connect with her on Twitter or Facebook.

No comments:

Post a Comment